Bach Reviews

Good Friends

In February of this year, we wrote about a series of pipe organ concerts held in the neighboring town of Streator, Illinois. We termed this two-day extravaganza, which featured seven magnificent instruments, "Candy for Your Ears."

As a result of that article, we recently received a two-DVD set that features some of the finest performances of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach that we have even heard, or seen. Thus we can only call this wonderful collection "Candy for Your Ears -- and Eyes." It is a treat to see and hear.

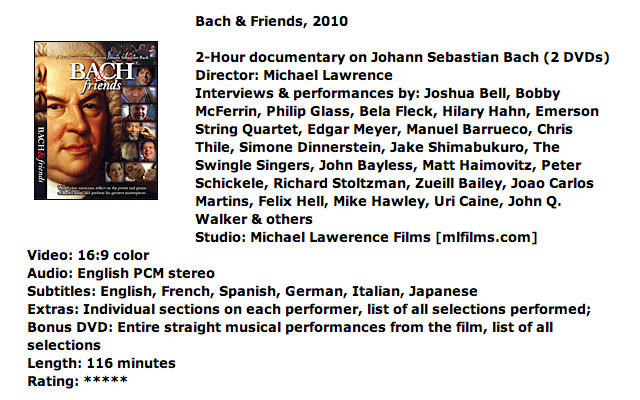

Titled "Bach and Friends," this two-disk set is the result of the cinematic skills of one Michael Lawrence, an accomplished filmmaker with many notable awards to his credit. Disk one is an approximately 2 hour-long documentary featuring interviews with and excerpts from performances by some of classical music's top talents; while the second disk contains the complete performances of many of those excerpted on the first.

We are not familiar with any of Mr. Lawrence's other projects, however, we would venture to opine that this set outdoes them all. It is a masterpiece.

It is a masterpiece for two reasons. First, consider the "friends" that Mr. Lawrence has chosen to showcase: Joshua Bell, today's reigning violin star; Felix Hell, the youthful virtuoso organist; clarinetist Richard Stoltzman, with more than a hundred CDs to his credit; dueling improvisational pianists, John Bayless and Dr. Anatoly Larkin; The Swingle Singers; and the inimitable Bobby McFerrin; the list goes on and on. All give stunning performances and poignant commentary on the meaning and influence of the works of the Great Man.

Unlike many classical music documentaries, Bach and Friends features a surprising number of diverse and young performers, all with awesome talent that will only become even greater as time goes by. It will be truly inspirational for young, high school and even earlier, budding musicians, who will see the value of the sacrifice involved in their at-home and before- and after-school practice sessions.

(The concept that classics are enjoyed only by senior citizens has always been misguided, as anyone who has ever attended a symphony concert will attest, and it is refreshing to see that this bogus bias has been so effectively destroyed by Mr. Lawrence.)

The documentary is also outstanding for its visuals. It has great performance value, with excellent lighting and camera placement. Mr. Lawrence clearly has an eye, as well as an ear, for music. As a result, Bach and Friends is as interesting visually as it is aurally. We see Felix Hell's feet literally dancing across the organ pedals in the D-Major Fugue, and even get a glimpse into the workings of the instrument itself.

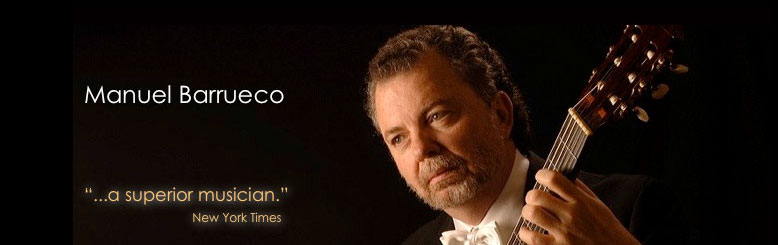

We see up close the incredible fret work of violinists Joshua Bell and Hillary Hahn, and cellist Matt Haimovitz: the dexterity of pianists Simone Dinnerstein and Hilda Huang; as well as unique interpretations of Bach's music by Chris Thile (mandolin), Jake Shimabukuro (ukulele), Manuel Barrueco (guitar), and Bela Fleck (banjo), even a surprisingly dynamic version of the Toccata and Fugue in D-minor played by Robert Tiso on something called a "glass harp," a collection of glasses filled with varying amounts of water to create different notes when rubbed or merely touched by his fingers.

About the only instruments lacking in this performance are the sitar and electric guitar. In an e-mail I inquired if Mr. Lawrence had considered including a heavy metal interpretation of something from the Bach repertory, as I have a nephew named Zack who's very accomplished with that powerful electronic contraption, and it would appear that some of Bach's riffs might prove a daunting challenge for rockers.

Mr. Lawrence replied that, although a big fan of classic rock (as are many classical enthusiasts, including this writer), he has not "found a rock player yet who is up to the high performance standards that I strive for, but maybe I haven't looked hard enough." Maybe he and Zack will get together someday.

The DVD set is also remarkable for the settings in which we meet and hear these performers. For instance, Richard Stolzman performs in the beautiful Church of St. Mary the Virgin, in New York. The Baltimore Basilica is the setting for cellist Zuill Bailey. Mr. Hell plays the magnificent organ at the Peabody Institute of Johns Hopkins University. And we listen to commentary by composer Philip Glass as he relaxes in his own New York City apartment.

Highlights, of which there are many, include the organ virtuosity of Felix Hell playing the Fugue in D-Major, a piece Bach composed while in his early twenties, about the same age as Felix himself; the sheer competitive joy in the faces of dueling pianists Bayless and Larkin as they improvise on "Sleepers, Awake:" and the emotion Joshua Bell brings to the plaintive Chaconne from the Partita in D-minor.

This is not music just for the classical devotee. This is music of universal value. In Bach's time there was not the dichotomy between classical and popular music that we have today. Bach was a star in his day, bringing new sounds and techniques to the world of music. One can be sure that, were he around today, he would be at the forefront of the musical scene, still creating and inventing new sounds and techniques that others of lesser skill would struggle to perform.

This year marks the 325th anniversary of Bach's birth, and a newly renovated museum has recently reopened in Leipzig, Germany. Excerpts from Bach and Friends are part of the permanent display at this refurbished museum.

This must-have documentary and performance set is not yet in stores, and is currently available only at mlfilms.com. The site also includes complete information on the performers, as well as critical reviews by professionals (which this reviewer emphatically is not). Classical devotees may want to visit this site immediately.

At a time when many schools are cutting back on their musical extracurriculars, Bach and Friends is an essential addition to any public or school library. It is a fine gift for any music lover, with something for the rocker and jazz enthusiast as well as the classically inclined; and a critical research tool for anyone interested in the development of Western music and its continuing influence on our culture.

Mr. Lawrence has produced a wonderful tribute to perhaps the greatest composer ever known. It has been widely hailed as a masterpiece by many professional music critics. In this documentary he shows not only that Bach has a great many friends of all ages, but is also making it easy for many more people to become a friend of Bach and enjoy his music.

By producing Bach and Friends and making it available to the public, Mr. Lawrence has not only given a great present to the Master on his 325th birthday, but has also proven that he is perhaps Bach's best friend of all.

David Mishur, OneOnlineCommunity.com| May 25, 2010

BACH AND FRIENDS: A TWO HOUR DOCUMENTARY ON JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH.

(A PRODUCTION OF MICHAEL LAWRENCE FILMS).

REVIEWER: JULIAN MINCHAM, 3/2/2010.

A new film about JS Bach is always going to be keenly anticipated by lovers of music around the world. This has certainly been true of ‘Bach and Friends’, a thoughtfully and affectionately produced two-DVD set by Michael Lawrence.

I have to begin by stating that I learnt nothing new about Bach or his music from the film, but to make this a criticism is to miss the point entirely. It is neither a documentary nor an educational treatise; it is a celebration and one that is, in my experience, quite unique. It records the reactions of a large and particularly diverse range of musicians to Bach’s music and through that, it honours it and rejoices at its legacy.

The film begins with a series of comments from the eclectic group of musicians as they strive to put into words what they feel about Bach and his music. I found this a moving experience and one with which I had great accord; how many times have we all struggled to express what is essentially inexpressible when it comes to talking about music? Perhaps the best way to give readers a taste of this is to quote a few of the comments (sometimes slightly paraphrased).

· There is something about Bach’s music that tells you things about the world that nothing else can.

· It is impossible to imagine a world in which Bach had not been born.

· There is such a humanity about Bach; he reaches the heart of human nature.

· Love of Bach is as close to religion as I get.

· It is as close as you can get to how a human brain and heart work.

Nor is it just comments of this kind that strike a chord (!). Look at the faces of these musicians as they play the music they love and note the range of backgrounds from which they come. Represented are people who play the piano, cello, violin, clarinet, tuned wine glasses, banjo, mandolin, double bass and ukulele! This film is not for the stuffy purist, but then how many people who are aware of the ways in which Bach himself transposed and transformed his own music, can afford to be snobbishly purist about it? Part of the message of this film is that Bach works well in virtually any medium or circumstance.

Sections of the film deal with difference ways in which Bach is received, studied and analysed in the twenty-first century. There is a focus upon the art of improvisation and neural studies of how the brain reacts when people are involved in this process. Glen Gould is upheld as one of the primary musicians who has influenced the way in which we listen to and receive Bach. There are sound recordings of his playing but, unfortunately, no film shots which, I assume, must have been caused by copyright problems. Eminent composers such as Philip Glass have some very thoughtful things to say about the way in which they feel that Bach must have conceived his music.

I had heard it said that some of the visual shots were gimmicky and distracting but with the single exception of some odd angles of a bass player’s fingers, I did not find this to be the case. Furthermore the producer has got around the perennial problem of people talking over the music (something which most musicians detest) by providing a second disc with the musical examples. All in all, you get quite a bit for your money.

I did, however, note a couple of strange ironies. The film makes a particular point of Bach’s own compositional range as well as the almost unlimited possibilities of media through which the music can be successfully transmitted. How odd then, to ignore completely the vast repertoire of choral music, the 200-plus cantatas, the passions, oratorios and masses. The repertoire around which the film is based is almost entirely instrumental. I know that you cannot cover everything in a two-hour film but could not we have had one or two singers and conductors voicing their views about this part of Bach’s output? Also ironic it seemed to me, was the thread of spirituality underlying many of the comments, and yet the music which many people believe was probably held to be the most ‘spiritual’ by the composer himself, was disregarded!

Perhaps there might be a further film centering on the 100 plus hours of this music?

Certainly the human side of Bach was not disregarded. There was the rather romantic picture of the family man putting his children to bed and retiring to his ‘closet’ with a glass of brandy to compose the works we cherish to this day! I am not sure if he did the former (there was usually more than one woman in the household charged with such duties) and what we do know of his composing room suggests it was rather larger than a closet. But as a metaphor it serves well; Bach did seem to straddle his domestic and professional worlds quite comfortably.

It was splendid to see Peter Schickele reviving some of the folklore about PDQ Bach (the arch-plagiarist who composed with tracing paper) and Ward Swingle who has been presenting energized Bach with affection for about half a century. I was strongly influenced by both of them throughout the early and middle years of my own career. The fact that Bach had a sense of humour and was a human being like the rest of us, albeit a rather special one, is something that does us no harm to be reminded of. Similarly, the excellent comment that, whilst placing Bach’s recordings in a space capsule to demonstrate to other civilizations the peak of civilisation attained on earth would simply be boasting, is an excellent reminder of the esteem in which the composer is held today.

This is a film for everyman (and woman) who likes, loves, has an interest in or simply wants to try to understand a little more of Bach’s music and the effect it has on people. Despite the couple of reservations I have expressed, it presents us with a wholly positive viewpoint and deserves a wide audience. I do not think that many will be disappointed.

I began by saying that I did not learn anything new about Bach from the film but perhaps that was a little unfair. I certainly did ascertain something about the various ways in which people receive and react to his music. Additionally, hearing it played on say, the mandolin, or the last sighing phrases of the Chromatic Fantasia breathed out of a clarinet, leads you to perceive it differently. And the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, even though Bach almost certainly did not compose it, sounds remarkably effective on wine glasses!

If I may be permitted to end with a personal reflection, when three close family members died in a very short time three years ago, I found that the greatest consolation was listening to, or playing, some Bach every day. There is something about his own experience of unremitting loss than transmits itself into the music and communicates in a wholly positive way at times of personal bereavement. But, like so much that the musicians struggle to put into words in this film, one can only encapsulate a part of the experience. The deepest things that touch us about music, Bach’s or anyone else’s, cannot really be communicated through mere words.

JULIAN MINCHAM, Posted on Bach Recordings group | March 2, 2010

There have been other filmed documentaries on Bach, but this is the best I’ve ever seen. We had a news item about it back in 2007. The list of performers playing and giving their own personal details and views about J.S. Bach is wonderful - most of them exactly the sort of performers I would have chosen if I were making such a film. The use of performers out of the straight classical genre is especially good; people like ukeleleist Jake Shimabukuro, mandolinist Chris Thile, jazz pianist Uri Caine, The Swingle Singers and multi-musical-generalist Bobby McFerrin give the documentary a more exciting and contemporary slant.

The mix of the actual musical performances with the commentaries by the performers and musicologists is very well done; getting some of the background of the composer’s difficult life in small bits in between the fine music is a good way to go. Then later you can enjoy the full performances on the second DVD if you wish. As a couple of the performers state, when they play Bach people who have no interest in or knowledge of classical music whatsoever get turned on and fascinated to hear more Bach. One of the pianists - Mike Hawley - turned out in the interviews to be superb at bringing viewers up to date on important details of Bach’s life, so that is his main job in the film, although he also performs one piano selection. Although I do have to disagree with his assertion that Bach was the center of European serious music life in his time; that honor went to Telemann. It seems at least a quick mention should also have been made about Mendelssohn’s hand in bringing the ignored music of Bach to the public’s attention. Whether viewers are into classical music or not, the film will convince them that Bach has been the most influential composer in history.

The cinematography is creative, with many unusual closeups of the performances, and striking environments - ornate European halls, beautiful studios, and in some a room in a NYC hi-rise with views of the skyscrapers in the background. The sound is also first rate - the Bach organ fugue performed by young Felix Hell (Reference Recordings) is both a visual treat with his amazing foot-dance on the pedals, but also an audiophile demo track with plenty of room-shaking deep bass and a fine pseudo-surround using ProLogic II. Thanks to Michael for using PCM stereo instead of DD.

I think my favorite performance in the documentary was classical/pop improviser John Bayless in a two-piano improvisation on a Bach theme. Altogether a terrific music documentary that should appeal to a very wide-ranging audience.

-- John Sunier

The Washington Post By Anne Midgette | February 11, 2010; 6:35 AM ET

Variations on Bach

The Bach Project is done. Culled from performances and interviews with leading and/or eccentric musicians, this film, a labor of love by the Baltimore-based director and composer Michael Lawrence, which when I last wrote about it in July seemed far from completion, is now cut, edited, and available on DVD.

It's hard to make a film about something that's very, very great, because the default mode tends to be a kind of awe-struck hagiography. Bach's music "tells you about life and the world in a way that nothing else can," the violinist Joshua Bell says to the camera, which doesn't say anything very specific about Bach or about what Bell feels Bach is telling is. Far more immediate is Bobby McFerrin, who explains how you have to let yourself go in Bach and sings an excerpt to demonstrate what he means about the music essentially being a dance: this is a prime example of music speaking louder than words to illustrate a point.

(read more after the jump)

It doesn't always; the film uncritically intersperses allegations of greatness with actual demonstrations of it. It's at its best when it moves beyond the "how great Bach art" theme, which is given a number of variations by the impressive roster of musicians who participated, and gets at the substance of the story.

This is not a documentary about Bach, but about how Bach is perceived and exists today through the eyes of musicians (and others) who have a special connection to the composer. Bach therefore ends up as a foil for a range of different topics. The question of improvisation, rightly identified as a key to Bach's work, leads to an MRI of the improvising pianist John Bayless that shows that different parts of the brain are activated when a player improvises than when he plays music that he knows by heart. An exploration of Bach and technology leads from the organ (once the most complicated machinery in the world) to Zenph Studios' recreation, on a contemporary player piano, of Glenn Gould's benchmark recording of the Goldberg Variations, to the video game creator Sid Meier, who wrote a computer program to compose music in Bach's style.

Running through all of this, behind the words, are some impressive Bach performances by the project's participants, including what the director says is Bell's only recorded performance of the Chaconne. As a fine perk, these performances are also offered on their own, without commentary, on a second DVD in the two-disk package.

The film treats its interview subjects with the same kind of reverent respect that they themselves accord to the composer they're discussing. In practice, this means that questionable statements are allowed to stand; some opaque statements remain unexplained; and there's only a light editorial hand. This isn't a film that wants to ask larger questions -- about the way, perhaps, that our society regards the music of composers who lived three hundred years ago; or about the period-instruments movement, which goes surprisingly unmentioned. The content is dictated by the subjects Mr. Lawrence found. The pianist Mike Hawley does provide a unifying thread, supplying various biographical details and anecdotes about Bach, speaking during the sections devoted to performers who evidently didn't want to speak themselves (like Robert Tiso, who performs the Toccata and Fugue in d minor, beautifully, on a set of crystal glassware filled to varying degrees with water).

Yet the participants take a definite second place to Bach in that they are identified only by their names, and their own words; there's no other indication of who they are. Philip Glass, Hilary Hahn, and the Swingle Singers are reasonably self-explanatory, but other speakers raise questions. The pianist Joao Carlos Martins speaks about losing the use of his hands, but doesn't explain what happened to him (his biographydoes, though). Hawley himself is an unorthodox MIT professor who runs the New Media Lab there and is a pioneer in an astonishing range of forms of digital technology; in the film, he is simply a performer and engaging narrator of stories of Bach's life.

In short, this is not a critical documentary but a love letter, given an additional glow by loving camerawork (a little overactive, sometimes zooming in to invade its subjects' personal space) and equally loving visual editing. And it does have plenty to offer: some fine performances; some interesting information; and what amounts to a cross-section of today's classical music world, in many of its current manifestations, from highbrow to crossover. It's up to the viewer to pursue the questions it raises or think about what it's actually saying.

By Anne Midgette | February 11, 2010; 6:35 AM ET

Dear Anne,

Mike Lawrence just forwarded me the link to your blog post. What a thoughtful piece. And thank you for the gentle words about "moi.". Since I'm writing, I should point out that it's "The Media Lab" at MIT (not the "New" Media Lab), and I didn't direct it --- I was a professor and led some big efforts for many years. Nicholas Negroponte was the director when I was there.

I've always been hugely supportive of Mike's efforts to make the movie, but I sure never expected to be IN it, let alone threaded through it. Basically everyone else is a superstar in some part of the music world --- I am just an amateur who loves to play. But, now that I've seen the movie, I'm really happy with the gentle, comfortable, warmly personal feel conveyed throughout. It's the first time I've seen myself on video and not squirmed. I think, like you, I like the refreshingly forthright quality of the movie, and the connections that emerge throughout. And when one person lays it on a little too hyperbolically, someone else just plays and smiles.

I'd like to do whatever I can to help the movie "grow legs.". If I were a kid in school, I'd love to have someone turn me on to this film. So if I can help you get word out somehow, just let me know. It's a special movie and I think a lot of people would love it.

Mike Hawley - February 11, 2010

Baltimore-based filmmaker Mike Lawrence has released a documentary on the music of Bach

and its wide-reaching influence. (Sun photo by Doug Kapustin / December 5, 2008)

Tim Smith, The Baltimore Sun | February 28, 2010

Three years after he started on the project, Baltimore filmmaker Mike Lawrence has released his latest documentary, "Bach & Friends," the kind of work that has "labor of love" all over it.

Lawrence's passion for Bach's music led him to ask a cross section of artists to discuss the composer's place in their creative lives. The result is an entertaining mix of ideas and emotions, along with music-making of a high caliber.

The two-hour DVD comes with a bonus disc with complete performances that are heard partially in the film.

With something like 30 interviewees crammed into "Bach & Friends," there's a certain level of unwieldiness to the product; that's a lot of talking heads. But Lawrence, who produced, directed and edited the film, generally maintains interest and flow, and except for some painful close-ups, there's enough variety of camera work and locations to keep the visual appeal strong. (Lawrence has entered the film in several festivals; premiere showings in Baltimore and other cities are in the works.)

A little more biographical material might have been useful for some viewers, and it might also have been wise to include a word or two of explanation about technical terms that get thrown around.

But by avoiding anything stuffy, the film has an appealing character that would make it a natural for PBS (it would even be ideal pledge week fare on that network, if only Lawrence had found some Celtic dancers heavily into Bach).

No one could miss the genuine enthusiasm and just plain reverence that the film's participants express. When pianist Simone Dinnerstein says that playing Bach is "as close to religion as I get," she's speaking for many musicians (even those who also have more traditional religious leanings).

Bach deserves his place high up on the altar of art, not just because of what composer Philip Glass describes as the "awesome amount, complexity and quality of the music," but also for the way that music suggests something ineffably spiritual.

Then again, you don't even have to get all celestial. Bluegrass mandolin virtuoso Chris Thile is just as effective noting how Bach's music just slams you "in the gut."

Thile lights up as he talks, reinforcing the fact of Bach's appeal not just across centuries, but musical borders, and he plays the heck out of a Partita transcription. The mandolinist also provides the perfect summary line for the film: "Everybody exposed to [Bach's music] in the right situation and the right frame of mind is going to love it."

Among the classical performers in the film, clarinetist Richard Stoltzman is especially eloquent in his remarks and his playing of a transcription of the D minor Chromatic Fantasy. Hearing such a work performed so persuasively and exquisitely on an instrument the composer didn't write for just reinforces the marvelous mutability factor of Bach's music.

That lesson is driven home as well by the disarming virtuoso Jake Shimabukuro, who clearly relishes the way Bach translates so effectively to "the underdog of all instruments" - the ukulele.

What Mozart called "the king of instruments," the organ, makes a compelling vehicle for Peabody Conservatory grad Felix Hell to focus on Bach's creativity. Classical guitar star and Peabody faculty member Manuel Barrueco makes an elegant contribution. Popular violinist Joshua Bell uses tried-and-true lines, referring to the Chaconne as "powerful and amazing," but his playing is anything but mundane.

The long list of musicians also includes stellar Baltimore-bred violinist Hilary Hahn; up-and-coming teenage pianist Hilda Huang (seen playing some Bach at a Baltimore home for seniors, a charming shot); and veteran keyboard artist João Carlos Martins, who has lost full use of his hands, but not his determination to keep Bach in them. A segment with the Emerson String Quartet tellingly includes the fugue Bach was writing before he died.

The amiable pianist and Massachusetts Institute of Technology faculty member Mike Hawley becomes a connecting thread for the film, weaving in insights and occasional biographical data.

A segment on improvisation goes on too long. A commemoration of pianist and legendary Bach interpreter Glenn Gould also drags, and turns into an ad for Zenph Studio, the software company that turns recordings into "re-performances" on a digitally wired piano. And, for all of Peter Schickele's enduring humor, there really isn't much point in having him talk about his classic invention, P.D.Q. Bach.

The film's major omission is Bach's vocal music (the inclusion of the Swingle Singers doesn't count). No mention of the B minor Mass or the St. Matthew Passion, and each church interior scene (Baltimore's Basilica makes a lovely appearance with cellist Zuill Bailey) only underlined the absence of the sublime sacred repertoire.

But it seems churlish to wish for more, since Lawrence has achieved so much in his film. By vibrantly exploring and celebrating Bach's hold on today's musicians, "Bach & Friends" makes it clear why the composer will continue to exert just as strong a hold for generations to come.

The two-DVD set of "Bach & Friends" ($39.95) is available from mlfilms.com

Tim Smith, The Baltimore Sun | February 28, 2010

Copyright © 2010, The Baltimore Sun

"There is something about the music of Bach that does transcend and it really makes you feel alive and it sort of tells you about life and about the world in a way that nothing else can." — Joshua Bell

"There's such a humanity to Bach and every possible human emotion from joy and humor and laughter to sorrow and loss and somehow reaches to the heart of human nature." — Matt Haimovitz

"My love for Bach and my feelings that I have are as close to religion as I get. I would say his music is kind of cosmic. You know, if you go and lie down in the country at night and you look up at the stars and you don't know what any of it means and you're just looking at this huge vista, I would say that his music is like that." — Simone Dinnerstein

"The music of Bach represents a sense of cosmic harmony, a sense of oneness with the universe. I can't help but think that he has lifted all of us up onto a higher spiritual plane along with his own striving toward that plane." — Eugene Drucker

These are just a sampling of the clips that launch us into Michael Lawrence's documentary film Bach & friends. It is almost two hours long and features an impressive line-up of contemporary artists, most of them soloists of the highest caliber

The documentary is weighty with adulation of J.S.B. and some astonishing performances of many masterpieces. The most jaw-dropping for me was organist Felix Hell's performance of the Fugue in D, S.532. You can hardly watch this guy's pedal work without falling out of your chair. Simone Dinnerstein's performance of the opening theme of the Goldberg Variations left me overwhelmed and breathless. The adulation and the performances are great. Even the stuff that flirts with kitsch (Bayless, McFerrin, the Swingle Singers) does not diminish the point of this film — Bach's music is great, and our lives are enriched by it from whatever direction it comes to us.

My only disappointment is that nowhere in the entire documentary is there even a mention that the greatest level of genius that Bach achieved (in the opinion of many) is in his choral works: the cantatas, the passions, the oratorios, and the B minor Mass — but had this body of work been addressed, it would have taken several more DVDs, so this is not intended as criticism of Lawrence's achievement, just regret. Still, I feel this set should have deserved at least an acknowledgement of the monumental vocal output of the cantor of Leipzig. Perhaps another time....

Bach penned everything he wrote in an unassuming consciousness that the God of his understanding was actually listening. Even the so-called secular pieces were sacred to him. It is in the solo works: the organ works, The Well-Tempered Clavier, the Goldberg Variations, the violin sonatas and partitas, and the cello suites that we meet Bach intimately and personally. Here we have one musician and one instrument communicating, first of all, with each other and then conveying meaning and aspiration to others who may be in the same space.

Bach's music was not separate from the man himself. Therefore when he and Maria Barbara lost both of their twins less than a month after they were born, all of the emotion of that monumental grief had to have found its way into his music. When Bach got down on the floor in rough and tumble play with his children, that too was expressed in his music. His passionate love life, his concerns about providing for his family, his conflicts with civil authorities, his taste for good German beer, his delight at the excellence of a new organ, his satisfaction in the accomplishments of his students — all of this had to find its way somehow into his music and especially in these solo pieces.

Of course Bach was an acclaimed organist, but he also was an accomplished player of the violin, the viola, the cello, the flute and more. One gets the impression in all the solo works that Bach was not "composing" but was instead writing down the instrument's part of the conversation as he worked out the meaning of human existence for himself.

In Bach & friends, there are a few insights into the character of Bach and how his personal makeup fit into and influenced the music he composed. This is not a documentary about Bach's life but rather a documentary about Bach's music and as such it provides an appreciable sampling of the music that is the foundation on which most of what we call music today is based.

The second DVD in the set is comprised of complete performances of the sample works without commentary or interruption. The sound and picture quality are superb. The editing flows comfortably. There is enough pure joy in this set to make it worth having on your shelf. It is in standard DVD format, not available in Blu-Ray or HD. The only purchase source at this point in time seems to be the website listed at the top of this review. If you are interested, there are several trailer clips on YouTube. Just go to the site above and it will lead you there.

by Ken Hoover

(c) 2010 CVNC.org, reprinted with permission of the author & CVNC.org.

I don't believe in the concept of greatest anything that you can't judge with measurable criteria: the longest opera, yes; the greatest opera, no. So the concept of Greatest Composer Ever in itself rubs me the wrong way. But make no mistake: if you do propose a GCE, you had better make it J.S. Bach, or I'll want to know the reason why you came up with somebody, at first glance, inferior.

Berlioz is one of the few major composers uninfluenced by Bach, whose "pupils" include Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Chopin, Debussy, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Hindemith, Bartók, Bloch, Shostakovich, Vaughan Williams, Gubaidulina, Schnittke, and so on. Who can believe such a legacy? Bach is also the despair of composers, just as Shakespeare is the despair of poets. You sense nothing of strain or struggle or (and this will sound funny) self-conscious artifice in his work, despite the considerable art and craft, and almost everything he wrote is at least twice as good as just about any work you care to name. Beethoven and Mozart sound like children in comparison, Wagner constipated, and Brahms a little dutiful. Furthermore, music poured out of Bach. I forgot how many thick volumes his output takes up, but consider that some scholars estimate about one-third of what he wrote has perished.

Every time I want to write about Bach, just as every time I want to write about Shakespeare or Sophocles, I feel even dumber than usual. I long to somehow achieve an epiphany of how he did it and realize of course that this boat will never land. Consequently, I'm slightly in awe of the courage of the participants in this documentary. Baltimore filmmaker Michael Lawrence gets a bunch of very fine musicians (and a couple of critics) to talk about what Bach means to them, both as musicians and in their "civilian" lives. Don't expect startling revelations, but you will get a very strong sense of exactly how big a deal Bach's music has become for some of the best performers of our time – a star-studded cast, in fact. I have no idea how he persuaded so many from the current A-list to appear. Furthermore, many of them perform complete pieces on the bonus disc. Joshua Bell plays the Chaconne. Hilary Hahn, unfortunately, plays only a snippet from one of the solo violin movements. Richard Stoltzman does an extraordinary job with just his clarinet on the Chromatic Fantasy for keyboard. When asked what he thought he could bring to the piece to make up for the necessary loss of parts, he replied, "I can give it breath." He does just that. Other musical highlights include a terrific young organist, Felix Hell and the Swingle Singers (led by their founder, Ward Swingle) in an a cappella "Badinerie" from the second orchestral suite. Jake Shimabukuro plays the 2-Part Invention #4 on the ukulele, and the spectacular bluegrass mandolinist Chris Thile goes to town on the Prelude from the Violin Partita #3 (a lively, danceable account – I wish violinists would play it that way). Finally, guitarist Manuel Barrueco delivers an astonishing fugue from the Violin Sonata #1 as if it posed no fingerboard problems whatsoever. You quickly stop waiting for him to stumble or hesitate and give yourself to the music.

As for the interviews, Philip Glass says nothing particularly interesting, at least not to me. Peter Schickele maintains the PDQ Bach fiction. Several people talk of improvisation as the basis of Bach's art. In a sense, it's probably true, since most composers begin that way. In Bach's case, however, it doesn't really account for the immense craft that he seemed to hold literally in his fingers as well as in his head. Bach had the ability to understand almost at once the contrapuntal possibilities of a theme. His son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, relates the story of the two of them attending an organ recital and the old man predicting the course of the fugal improvisation and nudging him when each prediction proved correct. It's not just improvisation, but an ability and a facility ultimately beyond our ken. It's effortless, because that's the only way it can happen at all. John Bayless contributes a couple of improvisations. Though Bayless plays well, you wouldn't mistake his products for Bach, even if Bach had an off-day and wore mittens.

For me, the two most interesting sequences come from pianists João Carlos Martins and Hilda Huang. Martins, a tremendous virtuoso in his youth who recorded an exciting account of the Well-Tempered Clavier, lost the pianistic use of both hands. In his interview segment, he plays the Largo from the Concerto in f almost like two-finger typing, and very beautifully. He tells the story of Bach's month in jail (Bach wanted to break his contract with his current noble employer), during which the composer began to write the WTC. This turn of adversity to something productive (and how!) became a source of inspiration to Martins. When he lost the use of his right hand, he told himself that he could play the left-hand repertoire alone. When he lost his left hand, he despaired, but eventually realized he could conduct. "Bach kept me alive." Hilda Huang (still with braces on her teeth) gives a surprisingly mature account of a Contrapunctus from Art of Fugue and talks of how Bach's music is more "internalized" than when she plays other composers and how, performing Bach at senior centers, she thinks of "rejuvenation and freshness." This from a twelve-year-old!

The DVD set currently is available only from the filmmaker. He plans eventually to put this in wider distribution, like at Amazon. However, plans, as we know, gang aft agley. If this CD interests you, hit the web site (see above) and pony up $39.95 for the two discs.

Copyright © 2010 by Steve Schwartz.

Thirty minutes in, however, the film loses focus during a discussion of brain activity during improvisation—material for an excellent PBS science feature—and becomes a praise-off as commentators offer up one superlative after another so that the film’s central inquiry becomes, “Bach is great, isn’t he?” Though Lawrence’s point of the versatility of Bach’s music includes an engaging performance by Robert Tiso of the Toccata and Fugue in D minor on glass harp, the point is over-emphasized in relation to the material oddly omitted; the film barely touches the depth of musical structure or impeccable order that would speak far more poignantly to the composer’s genius.

Ironically, the essence of Bach’s music is articulated best by those musicians who use the fewest words. Mandolinist Chris Thile and cellist Matt Haimovitz speak about the transcendent joy of performing Bach in nontraditional spaces. Bassist Edgar Meyer marvels at the technical challenges for the musician while giving a masterful performance of the Prelude to Suite No. 2 for Unaccompanied Cello. Banjoist Béla Fleck, in his soft-spoken manner, summarizes the statements by half a dozen previous commentators: “I just know that I like it.”

The film’s final sequence is its best, featuring The Art of Fugue. Here, finally, Lawrence artfully fuses the life and music of Bach in the performance by the Emerson Quartet. The foursome “disappear[s] into the music,” in the earlier words of Bobby McFerrin. One wishes the documentary did the same. Not surprisingly, the star of the film remains the music; the performances are a delight, and a second disc of uninterrupted performance footage is included with the DVD.

Elliot Mandel, Chicago Classical Music | March 4, 2010

For Love of Bach

The Music Scene: Donald Sosin

March, 04, 2010

There is surely no composer whose work transcends cultural, geographical and temporal boundaries as does Johann Sebastian Bach’s. Just in time for the 325th anniversary of his birth on March 21, comes a terrific new 2-DVD set celebrating many facets of his work.

The brainchild of Michael Lawrence, a conservatory-trained guitar and banjo player turned award-winning documentary filmmaker, “BACH & friends” features performances and interviews with leading musicians including Bobby McFerrin, Simone Dinnerstein, Edgar Meyer, Philip Glass, Peter Schickele, Richard Stolzman, Hillary Hahn, the Swingle Singers, Béla Fleck, Matt Haimovitz and the Emerson Quartet. The first DVD contains the musicians’ commentary interspersed with musical clips, along with keen insights from pianist/scholars like Mike Hawley, who contemplates what the world would be like had Bach not lived, perish the thought.

On the second disc are the full performances, including Felix Hell’s brilliant D major Fugue rendition, and the only recording of violinist Joshua Bell playing the exalted “Chaconne” from the Partita No. 2. Dinnerstein’s look at the “Goldberg Variations” is especially poignant, and her playing evokes the standards set by the formidable recordings of Rosalyn Tureck and Glenn Gould. Regrettably, there is no example of Tureck’s on this release (although there are clips of her playing online as part of guitarist Sharon Isbin’s interview, which is in a planned sequel. Follow links at mlfilms.com). Gould shunned live performances for much of his later career, but you can see him playing “live” on this disc as well.

My grandfather once told me of his amazement at hearing a concert at New York’s Town Hall with an Ampico, an early electronic device which, unlike a player piano, did not just duplicate the notes played, but recorded and played back the minute changes in pressure and velocity of the keys as a pianist played, and was able to reproduce those subtleties through its mechanism. John Q. Walker of Zenph Studios has brought this concept into the computer era through analyzing audio recordings and converting them into “a description of how the musician played the day it was recorded.” Every facet of the original (except for Gould’s idiosyncratic humming) is preserved this way and the result is fascinating and a bit spooky.

“The Bach Project” explores the enormous variety of Bach’s music and its adaptability to instruments he never wrote for, such as the banjo and well, the piano. There are a few omissions: no vocal music, nor any reference to the harpsichord, to Wanda Landowska, or the importance of her work in reviving Baroque music in general. And a couple of misfires, such as the gaudy 4-hand improvisation by John Bayless and Anatoly Larkin on the “Sleepers Awake” theme that crosses over into Liberace territory, complete with head rolling and hair tossing. On Disc 2 Bayless does his version of “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” combined with “Amazing Grace,” which is more pleasant to the ear if not to the eye. But by and large, this is an absorbing and elegant documentary that ought to be shown in music classes, and on PBS.

The high point of the film for me is the stunning final segment in which the Emerson Quartet discusses and plays part of Bach’s last, unfinished work, “Art of the Fugue.” Here the sounds are coupled with computer-generated fractals that evoke the distant reaches of space, to which Bach’s music has been sent on the Voyager I spacecraft.

Samples of all this material, including extra footage, are online (along with a link to purchasing the DVDs, $39.95 plus shipping), at mlfilms.com. A free public screening of the 2-hour documentary will take place at Noble Horizons in Salisbury, March 21, at 3 p.m.

Another Bach celebration takes place the night before with Close Encounters, March 20, at 6 p.m. The program features cellist Yehuda Hanani, violinist Cordelia Hagmann and pianist James Tocco in an an all-Bach pre-birthday celebration that includes many transcriptions from the Romantic era. Tickets at cewm.org or at the Mahaiwe in Great Barrington, MA.